Lead (Pb) is a very stubborn metal. When a lead particle enters our body it readily replaces a calcium or zinc particle and becomes stuck very firmly within our tissue. In nature, lead is an uncommon heavy metal which is found at a concentration of only 10 parts per million in the earth’s crust1. However, over the past few decades lead has become much more prevalent in day-to-day life and toxicity has become a common problem as a result.

Symptoms of Lead Toxicity

Lead-poisoned adults may develop anemia, digestive issues, kidney compromise, sexual sterility, convulsions2, depression, anxiety and memory loss3, while children may suffer from abdominal pain, constipation, nausea, reduced IQ, limited growth and delayed sexual maturation4. However, symptoms typically don’t present until very high levels of lead have accumulated in the body5.

Sources of Exposure

Because of its moldability, resistance to corrosion and low cost, lead is a widely used metal in industry and manufacturing processes. Lead toxicity most often occurs from exposure to contaminated soil, water, plumbing, lead paint and car batteries6.

Lead enters the body most through inhalation or ingestion of contaminated dust. Lead affects both adults and children but children are especially vulnerable due to their significantly increased absorption of the metal7.

Lead in Nova Scotia

Significant sources of lead exposure to Nova Scotians include contaminated drinking water, the manufacture of batteries and paint from some older homes8. There has been media attention over the past few years on lead contamination of drinking water of Acadia University9 and Kings County Academy10. The death of eagles from lead poisoning here in Nova Scotia has also been reported by the CBC11 and The Chronicle Herald12.

Chelation Therapy

The standard and only proven effective treatment for lead toxicity is chelation therapy. Chelation involves giving a medicine (chelator) which latches onto a specific compound and allows it to be mobilized and removed from the body. The standard chelating agent used for removing lead is intravenous EDTA (Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid), with oral DMSA (Dimercaptosuccinic acid) being used in some cases. Because lead binds very tightly within our tissues, especially bone, chelation is necessary to dislodge and remove it from the body.

The number of chelation treatments required to reduce heavy metals down to a healthy level depends on the total body burden of the metal, i.e.: the total amount of the metal within the body. Treatments are typically given once every 1-2 weeks for 10-20 treatments to sufficiently reduce the total body level of the target heavy metal.

Safety of Chelation

When administered by a properly trained practitioner, chelation therapy is very safe13. Chelation therapy can temporarily lower blood sugar so eating a snack before, during or after treatment helps prevent any fatigue or light-headedness which may occur as a result. Chelation therapy can and should be used to treat advanced cases of lead toxicity during pregnancy14.

Assessing For Lead Toxicity

Blood tests

Heavy metal toxicity is typically tested through blood testing. The current upper limit for blood lead concentration recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)15 is 5ug/dl (micrograms per decilitre) for children and 10ug/dl for adults. However, adverse effects have been associated with much lower levels in the blood16, 17, 18, 19, 20. Also, the World Health Organization6 has recently stated that there is “no known level of lead exposure that is considered safe.” Blood testing is reliable for identifying acute lead poisoning but is not reliable for diagnosing long-term toxicity. According to the CDC, blood tests “under-represent the total body burden because most lead is stored in the bone”21, rather than in the blood.

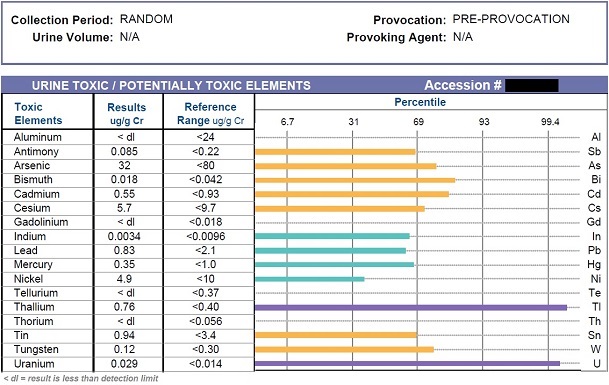

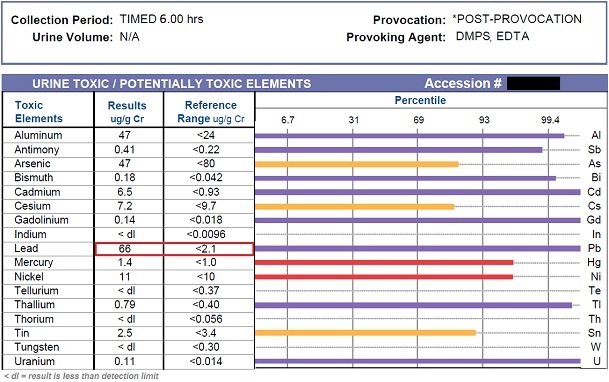

Chelation Challenge Urine Tests

The problem of the lead blood test is solved with the EDTA chelation challenge urine test. A chelation challenge with EDTA involves mobilizing a percentage of the lead from within the body and measuring its concentration in the urine over the following 6 hours. The concentration present in the post-chelation urine is a very good indicator of the body’s total burden of lead and other toxic heavy metals sequestered within the body.

Lead Toxicity Prevention

There are a few important ways which you can reduce your exposure to lead including avoiding contaminated products, being aware of your occupational exposure22 and by limiting exposure through drinking water. Reducing lead exposure from drinking water here in Nova Scotia can be achieved through a few simple steps:

- Use cold water for cooking and drinking,

- Run the faucet for 5 minutes prior to drinking or cooking if the faucet hasn’t been used for 6 or more hours,

- Clean all faucet aerators periodically and

- If pregnant or if you have children consider using a NSF-53 water filter to significantly reduce lead levels in your drinking water.

If you are in the Halifax area you can contact Halifax Water23 to have your drinking water tested for the presence of heavy metals.

Chelation Therapy in Halifax

If you are interested in receiving chelation therapy and are located in the Halifax area, please contact MacLeod Naturopathic to book an initial naturopathic visit with Dr. MacLeod to discuss your options.

References

- Jefferson Lab. “The Element Lead.” It’s Elemental. Web. 27 Jan. 2015.

- Staudinger, K, Roth V. Occupational Lead Poisoning. Am Fam Physician. 1998 Feb 15;57(4):719-726.

- Mason LH, Harp JP, Han DY. Pb neurotoxicity: neuropsychological effects of lead toxicity. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:840547.

- Warniment C, Tsang K, Galazka SS. Lead poisoning in children. Am Fam Physician. 2010 Mar 15;81(6):751-7.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. “Lead Poisoning.” Symptoms. The Mayo Clinic, 10 June 2014. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- World Health Organization. “Lead Poisoning and Health.” WHO. Oct. 2015. Web. 26 Jan. 2015.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Toxicology. Recommendations for the Prevention of Lead Poisoning in Children. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, 1976.

- Nova Scotia Occupational Health And Safety. “Occupational Health and Safety.” Novascotia.ca. Aug. 2001. Web. 28 Jan. 2015. .

- Rhodes, Blair. “Acadia Water Fountains Test Positive for Lead – Nova Scotia – CBC News.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 11 Sept. 2013. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- Delaney, Gordon. “Getting Lead out of School’s Water Still Proves Challenge for N.S. Staff.” The Chronicle Herald. 7 Jan. 2012. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- CBC News. “Lead in Bullets Poisoning Eagles, Says Vet – Nova Scotia – CBC News.” CBC News. CBC/Radio Canada, 13 June 2012. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- Gorman, Michael. “Lead Poisoning Threatens Eagles.” The Chronicle Herald. 3 Jan. 2012. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, Mark DB, Rozema T, Nahin RL, Lindblad L, Lewis EF, Drisko J, Lee KL; TACT Investigators. Effect of disodium EDTA chelation regimen on cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: the TACT randomized trial. JAMA. 2013 Mar 27;309(12):1241-50.

- Shannon, M. Severe Lead Poisoning in Pregnancy. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2003;3:37 39.

- National Center for Environmental Health. “What Do Parents Need to Know to Protect Their Children?” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 19 June 2014. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- Ha M, Kwon HJ, Lim MH, Jee YK, Hong YC, Leem JH, Sakong J, Bae JM, Hong SJ, Roh YM, Jo SJ. Low blood levels of lead and mercury and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity in children: a report of the children’s health and environment research (CHEER). Neurotoxicology. 2009 Jan;30(1):31-6.

- Eum KD, Korrick SA, Weuve J, Okereke O, Kubzansky LD, Hu H, Weisskopf MG. Relation of cumulative low-level lead exposure to depressive and phobic anxiety symptom scores in middle-age and elderly women. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Jun;120(6):817-23.

- Work Group of the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. “A Review of Health Effects of Blood Lead Levels. 23 Feb. 2004. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- Lee WR, Moore, MR. Low level exposure to lead. BMJ. Sep 15, 1990; 301(6751): 504–506.

- Olympio KP, Gonçalves C, Günther WM, Bechara EJ. Neurotoxicity and aggressiveness triggered by low-level lead in children: a review. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009 Sep;26(3):266-75.

- Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. “Environmental Health and Medicine Education.” Lead (Pb) Toxicity: What Tests Can Assist with Diagnosis of Lead Toxicity? N.p., 20 Aug. 2007. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- “Code of Practice: Working with Inorganic Lead.” Nova Scotia Labour And Workforce Development. N.p., 12 June 2010. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.

- “Water Quality and Lead.” Official Website of Halifax’s Municipal Government. Web. 28 Jan. 2015.